John Lennon’s Last Days: A Remembrance by Yoko Ono

BY YOKO ONO

DECEMBER 23, 2010.

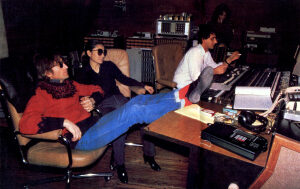

Making Double Fantasy was a great joy for John and me. But it was intense as well, since we were trying to finish it for the Christmas release. John knew what I was up against and protected me to the end. If it weren’t for that, the record would not have been a dialogue between a man and a woman. But if the record was not a dialogue between a man and a woman, John would have refused to do the record at all. That’s how it was.

Nobody was unkind to me. But there was a strong feeling that this record should have been just John, and I was an extra thing that they had to put up with. I hear a big yes! from you guys who are reading this. So you must understand how people at the time also felt.

Because of that delicate situation, John had to do his own thing and protect me at the same time. Even with his quick, astute observation and total power in the studio, that was not easy. He was trying to protect a proud lioness with a sheep’s heart, without so much as letting her know that’s what he was doing. Now, looking back, I get that as clear as a bell.

By the Double Fantasy sessions, I was pretty used to how you do it in rock. But in a pressured situation, I went back to being my old classical avant-garde self. A guitarist was having a difficult time finding a good solo for one of my songs. It was late at night and I just quickly wrote musical notes on a piece of paper and asked him if he would play that for the solo. Sometime before that, I had been told by someone that he read music. So I thought it was more polite to give him a scribble of musical notations than showing him what I wanted on the piano, in which case the whole group would know what I was doing. He just said, “I can’t play this,” to John. John looked at me, looked at the guitarist and left the room, beckoning me to follow him. Outside the control room, he said, “Remember? You should whisper to me!” I should whisper the music line in John’s ear?! But in rock, you don’t criticize the musicians for their solos. You just say, “That was good. But could we have one more, just in case? A bit lighter, possibly …” Something like that. So I knew I made a faux pas. I just said, “I know, I know,” and let it go. That was that.

Then there was “Yes, I’m Your Angel”! I wanted to do it in 3/4. John said, “Let’s do it rock, 4/4.” So we did it in 4/4. When we finished all the tracks, John said, “So we did it! Anything, Yoko?” I told him that I actually still wanted to do “Angel” in 3/4. “Oh … right! I never should have opened me mouth! So let’s get them back.” The musicians had all packed and left the studio already. Andy, the drummer, had to come back from Bermuda! But we did “Yes, I’m Your Angel” in 3/4. The problem was, the one we did in 4/4 sounded much better. The musicians played both 4/4 and 3/4 versions perfectly. So it was not their fault. Something about doing it in 3/4 was so predictable for this kind of song, it sounded more contrived than the 4/4 version, which surprised us as being more fresh when compared with the 3/4. So we went back to using the 4/4 we did anyway. The musicians were all gracious about it, but I don’t think I won any popularity contest or anything! I thought nothing of that at the time. Artists have the right to aim for perfection. But now I see that John was helping me, without making a thing about it.

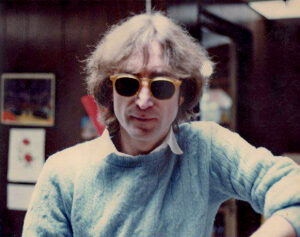

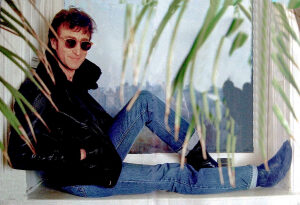

One day, in the middle of making Double Fantasy, the engineers told us they needed two hours to fix the board. So we should go out for a while. Take a walk. Great! After being in the dark studio for ages, the outside made us squint. It was like spring! A beautiful, beautiful day. The sky was shining blue. We felt like two kids skipping class. John decided that we would go into Saks Fifth Avenue. He went through a few counters and stopped at the glasses: “We should get one for you.” He picked a pair out — large black wraparound shades — and put them on me. Strangely, he started to look rather serious. “What?” “You should wear these all the time.” I thought that was silly and wanted to laugh, but stopped short. He was gazing. It reminded me of the first time I saw him gazing at my “Painting to Hammer a Nail In” in the Indica gallery. This time he was gazing at me wearing the glasses he picked for me. “Why?” I asked with my eyes. He just took my hand and we walked quickly toward the exit. It was time to go back to the studio. I immediately forgot the incident totally. Later, those were the glasses I wore to face the world. I heard John saying, “Keep your chin up. Never let them know that they got you!” So even after his passing, he was still protecting and helping me.

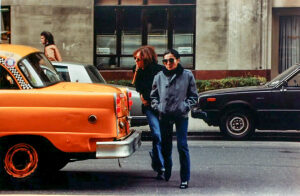

We were both very verbal people. Once we were on the elevator talking away, and forgot that we didn’t push the button. The elevator was still on the ground floor for the longest time without us noticing. Finally, the door opened and a lady came in and we noticed what we did. We were just chatting away. Why did we have so much to talk about? Maybe because it was just the two of us. We burned the bridge, and we didn’t have anybody else except each other. John didn’t mind that at all. It probably had to do with the fact that he had met and shook hands with so many people in the Beatles’ tour days, not seeing people so much felt fresh.

We were also very silent people, too. We didn’t have to say anything. Just by looking at each other we knew what the other was thinking. The more the world hated us, the more we became fiercely protective of each other. I loved the way he looked toward the end: “Keep your chin up. Don’t let anybody see that they got you!” I always nodded when he said that. But when he was alone, I caught him pondering with a faraway look of a young/old soldier who remembered it all. One day, he even said, “Look, if I ever die, make sure to …” and he gave me precise instructions on what I had to do to the Beatles’ outtakes. “Make sure to do that.” I thought it was remarkable that he was still concerned about his old takes. Artist to artist, I liked that remark at the time.

One night, he was sobbing. “Don’t leave me alone. Don’t die on me.” “But, John, I’m older than you, so it’s natural that I go first.” “No, you can’t. You just can’t.” But another day he said very calmly, “If you died, I’m going to make a soup out of you, and drink it. We will finally be one body then.” He seemed to have been inspired by that idea, and said it to people who were working for us. “You know, if Yoko died, I’m going to make a soup out of her, and drink it ….”They all looked stone-faced, as if he didn’t say anything unusual. John sounded like a little boy when he was saying that. A little boy who thought of a great idea.

The two of us as a couple were not very popular, to put it mildly. Everybody around us seemed to be thinking if it weren’t for John being with me, the Beatles would get back together again. While we were separated, John told me that he had to do an interview to say that the Beatles could get back together. He told me that the record company felt they had no chance to sell his record if he hadn’t done that. So he did an interview and sent a copy to me. When you watch that famous video interview, you see that John was being rather awkward. He tried to be funny — that was always an out. For a guy like John to finally do an interview he didn’t believe in, he must have felt really pressured. I thought if we separated, maybe he will get back to being the popular guy he had once been. That was not the only reason I wanted the separation. I had enough, too, of being hated by everybody in the world. The situation was hell. It was getting dangerous for me. For John, it was affecting the sales of his albums. That meant a big dent in his career. I felt guilty. But John was gung-ho about us being together. So we went back to sit in hell and enjoy it. Hell! What’s hell?

“We’ll be happy wherever we are as long as we are together. Do we care? No, Yoko. We don’t, do we? We’ll be on rocking chairs in Cornwall when we get old, and wait for Sean’s postcards.”

In the Double Fantasy period, he got his creative juices back, and was totally alive writing great songs and recording them. But in the middle of the night, he was having nightmares of us separating again. This time, by death.

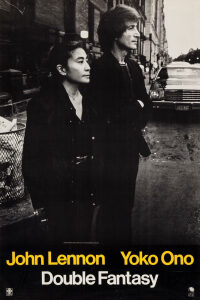

I did the artwork for the Double Fantasycover. I selected a good font for the words. And I used two photos by Shinoyama for the front and back of the LP, except I made them black and white. The original photos were in color. I thought it would reflect the grittiness of the album by making it black and white. I thought it would send the message out that it was a documentary and not fiction. But “Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans,” as John said. When I look at the cover now, I wonder if there was more to the story in making it black and white that was not in my calculation.

The album was finished. We put out the single “(Just Like) Starting Over.” But the single did not go to Number One. I went to John, who was sitting in a comfortable chair reading the papers. “John, I’m sorry. The single only went to Number Eight.” “It won’t move?” “No.” He was thinking for a second, looking at me. Then he said, “It’s all right. We have the family.”

He had grand plans if the single went to Number One. Being English through and through, John had planned to take Sean and I to England on the QE 2. He wanted to show Sean to Aunt Mimi, and also say hello to Liverpool. But now we had to chuck that plan altogether.

The last weekend was very quiet. The sky was cloudy in a restful way. And the town seemed as though it was asleep.

Saturday started with John listening to “Walking on Thin Ice.” As John was so focused on it, I went out to the newsstand and suddenly thought I should get John some chocolates as a surprise. He loved chocolates, but it was not in our sugarless diet at that point. After the drug binges of the Sixties, John wanted both of us to clean up and be healthy “for Sean’s sake too.” But that Saturday, the last Saturday John would enjoy, I thought of getting him some chocolate and surprising him. I don’t know why I thought that. I didn’t like chocolates at all then, so I wasn’t suffering not eating them. I got some and came home. As I came out of the elevator, I was surprised by John opening the door to the apartment before I rang the bell. “How did you know I was coming back just now?” “Oh, I know when you’re back.” He was so happy that I got him the chocolates. I remember how he smiled.

The same day, John wanted all my artwork to be brought upstairs from the basement to the white room. This was not the first time he asked for it, but he asked for it on this weekend again. “It’s ridiculous. We have those great works, and we are leaving them in the basement. I want to enjoy them.” For me, it was boring to have to see my old works every day. As a result, my pieces were piled up in the basement storage covered in dust. In those days, I didn’t particularly care about that. “John, can we do it after we finish the album? We are all so busy now.” “No, we should do it now. You’ll never do it otherwise.” As he said it, there was a touch of sadness in his voice, as if he already knew we would never bring them upstairs. We didn’t.

All day, John did not stop playing “Walking on Thin Ice.” He played it over and over again. We still hadn’t overdubbed the guitar solo, so I thought he was checking what to do with it. But it was unlike him that he took so much time on it. I went to sleep. When I woke up on Sunday morning, he was still playing “Walking on Thin Ice,” as he looked over the park. I knew the song was a good song. But I was just thinking of what else should be done musically. Never thought deeper than that at the time. Only just recently, it occurred to me that maybe John was aware of the song in a different light.

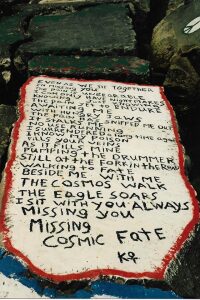

Walking on thin ice

I’m paying the price

For throwing the dice in the air.

But it goes into the middle eight after the second verse:

I may cry someday,

But the tears will dry whichever way

And when our hearts return to ashes

It’ll be just a story.

I hadn’t realized that it said “I may cry someday,” not “YOU may cry someday” or “WE may cry someday.”

What was I thinking?! John probably noticed it as he listened to the song that weekend, so intently. Was that what made him keep on listening? Did we know something? John? Me? Death was one thing we didn’t discuss that weekend. But it was around us like a thick fog.

The last Sunday. I’m glad in a way that we didn’t know that it was our last Sunday together, so we could have had a semblance of normalcy. But it turned out that it was not a normal Sunday at all. Something was starting to happen, like the dead silence before a tsunami. The air was getting tenser and tenser, denser and denser. Then, I distinctly saw airwaves in the room. It was wiggly lines, like on the heart monitor next to the hospital bed, just before it becomes a flat straight line. “John, are you all right?” I asked through the density. He just nodded and kept listening to “Walking on Thin Ice,” playing it loud. Walking on thin ice. Walking on thin ice .. . “John, John, arrre youuuu alllll riiight?” I heard my voice vibrating. I could not go near John, for some reason. WALKING ON THIN ICE. WALKING ON THIN ICE. WALKING ON THIN ICE. I realized that both of us were in a strange dimension in a weird time zone, as if we were in a dream. Then it all stopped. I went into a long and shallow sleep, with John over me, kissing me tenderly.

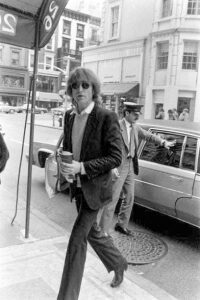

Monday. The very last day of John’s life, we woke up to a shiny blue sky spreading over Central Park. The day had an air of bright eyes and bushy tails. John and I remembered that we had a full schedule. Annie Leibovitz’s photo session, RKO radio show, and studio work from 6 p.m. John liked being prompt. John was English, I was Japanese. The result was both of us possessed extreme austerity and hilarity back to back. The sky was turning gray in the afternoon. And John kept talking to the RKO radio guy, cramming in a lot of things. We nearly became late for the studio. I rushed into the car and saw John still signing an autograph for a guy in front of the Dakota. “John, we’ll be late!” I remember being a bit irritable. “Why one more autograph?” I thought. John said something like, “OK,” and rushed into the car, sat next to me and held my hand as usual. The car drove off.

I know I speak of his hands a lot. I loved his hands. He used to say he had wanted hands like Jean Cocteau — long and slim fingers. But I grew up surrounded by cousins with those aristocratic hands. I loved John’s, clean, strong, working-class hands that grabbed me whenever there was a chance.

The studio work went until late at night. In a room next to the control room, just before we left the studio, John looked at me. I looked at him. His eyes had an intensity of a guy about to tell me something important. “Yes?” I asked. And I will never forget how with a deep, soft voice, as if to carve his words in my mind, he said the most beautiful things to me. “Oh,” I said after a while, and looked away, feeling a bit embarrassed.

In my mind, hearing something like that from your man when you were way over 40 … well… I was a very lucky woman, I thought. Even now, I see his piercing eyes in my mind. I don’t know why he decided, at that very moment, to say all that as if he wanted me to remember it forever. Did it matter that the whole world hated you if your guy loved you that much? Who cares if you had to live in hell with him? Some couples might be lucky to live in heaven. John and my heaven was in Hell. And we loved it. We would not have wanted it any other way.

Yoko Ono

London, October 18th, 2010